Sean Docking is a physiotherapist and research academic at Monash University in Melbourne. Both his clinical and research work focuses on lower limb tendinopathy, particularly patellar and Achilles. Recently he gave a presentation that I was lucky enough to see and wrote the following summary.

- What is tendinopathy?

It affects many tendons and many different types of people ranging from inactive individuals to elite athletes. Tendon pain is focal localized pain – the pains doesn’t move and there is no referred pain as such. Pain is load dependent – as load increases then generally the pain should increase also. Pain usually is worse the day after loading and something to look out for as a marker of tendon pain. Tendinopathy is NOT tendinitis – as there are NO inflammatory cells – this is important to know as it will govern the type of treatment.

The Continuum of tendon pathology (outlined by Cook & Purdam) tried to put the pathological changes in a sequence to ascertain what was going on with this injury type. This process was then further summarised by Sean: Within the tendon you start off with brown collagen fibres with very little water between tendon fibres. With the onset of this injury type we get an increase in tenocytes and an influx of inbound water into the tendon which causes the tendon to thicken and partially separate. Then as this continues we start to get disruption in collagen fibres and then blood vessels grow into the spaces where separation has occurred. Key message here – This is a cell driven pathology as the tenocyte has such control of the extracellular matrix that it is driving these pathological changes – Sean calls it “ an angry cell!”

Sean then went on to describe the sequential stages a tendon goes through when injured and how they can be imaged. Reactive tendinopathy is where very little change in the fibrillar structure. If we excessively overload our tendon it will get to this initial stage. We can easily transition back to a normal tendon by calming down the cells and removing the bound fluid within the tendon. It is a recoverable tendon if you can intervene early enough. Next you can shift into Tendon disrepair and if you continually overload a tendon in the reactive stage then this is how your tendon reacts . It is still possible to repair if the disruption isn’t too excessive. Finally you may reach Degenerative tendinopathy where this is very difficult to go back to being pain pain free or back to a normal tendon. The main aim in this stage is to build up the tendon as much as possible and be able to deal with the loads that are given with limited pain.

- How do we image Tendons?

– Ultrasound or MRI is commonly used by practitioners to identify tendinopathy. MRI is most useful as it gives a 3D image of the structure and surrounding aspects of that tendon structure.

– The Issues with these modalities is that ultrasound is highly user dependent as the transducer tilt can effect results and relies on subjective interpretation. This is also the case for MRIs but to a lesser extent. This allows for little ability to monitor change over time and details can be missed.

-Ultrasound Tissue Characterisation (UTC) is a technique that reliably quantifies the structure of the tendon using a transducer over the length of the tendon to produce 3D image of the area. This allows effective comparisons between changes in the tendon using repeat scans. This technique is also effective in detecting mixed pathology of a tendon. Mixed Pathology most commonly presents itself as degenerative tissue with normal tendon surrounding it. If pushed to the limit then this can change in that the normal tendon tissue will then move into a reactive tendon phase. This was previously not detectable until the introduction of UTC imaging.

– Why else is this important though? By identifying the structure of the tendon it is helpful in detecting injury or injury risk. For example, you can present pathology that is not painful. Common examples of this occur in the patella tendon. Having a structure abnormality though does increase your risk of developing an issue in the future. Therefore by highlighting these structural differences with the use of techniques, such as UTC, practitioners can implement techniques to mitigate further degeneration of the injury.

- Associated Risk factors?

-Age plays a factor with the Achilles as the older you are the more likely you are to be at risk of injuring this tendon. For the Patella tendon this is primarily seen from 16yrs to late 20s.

-Tendonopathy is most prevalent in Males: Estrogen is protective for our tendons so that is why we see less in females. Therefore, if a female in her early 20s has been diagnosed with patella tendonopathy then you should question that diagnosis. This only occurs when tendon is greatly overloaded.

-Genetic predisposition: The COL5A1 gene is associated with tendon stiffness and generally helps you to be a better athlete but makes you more susceptible to tendonopathy.

-Adiposity: Waist circumference over 83cm increases the risk of having tendonopathy.

Application to the High Performance Environment:

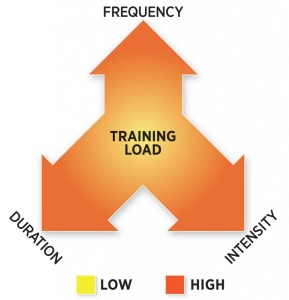

-Overall, load is what causes tendons the most stress and tests the tendons capacity. You can change your tendon capacity based on the loads you frequently expose it to (E.g. Low Vs Medium Vs High tendon loads). The higher the loads occur the faster the tendon is working which involves movements like plyometric and changes of directions at speed.

-Considering Preseason loads: many injuries occur at this stage of training due to continually consistent high loads with limited recovery. So if we know this why not modulate the loads using periodization? Ofcourse there comes a time for functional overreaching – however appropriate recovery sessions and days off should be implemented during this part of the season.

–Key message: if we get the load right then the tendon structure will improve – However there is a tipping point and we need to find this early on and identify appropriate actions to mitigate risk.

-It is important to gradually increase loads as major changes are not good for tendons. Also, if you completely drop the load for too long then you will lose tendon capacity. Practioners may sometimes want to rest the injury due to pain but this is an adverse practice. The tendon needs constant stimulus – endevour to keep load on the injury as the tendons capacity will closely mirror the loads that it is exposed to.

ty (HRV) and Resting HR. How do you know where a player is at in regards to how they were a few weeks ago? For Darren HRV is a test that gives him a good assessment of his players stress. It can tell him that a player is stressed from training, everyday first world problems, or the onset of overtraining. It is then his job to find the source of the stress and then get rid of it if possible. This can be a useful tool if everything is kept constant in regards to athlete compliance and how the testing process is completed.

ty (HRV) and Resting HR. How do you know where a player is at in regards to how they were a few weeks ago? For Darren HRV is a test that gives him a good assessment of his players stress. It can tell him that a player is stressed from training, everyday first world problems, or the onset of overtraining. It is then his job to find the source of the stress and then get rid of it if possible. This can be a useful tool if everything is kept constant in regards to athlete compliance and how the testing process is completed.

factors based on each individuals performances and team performances. Then using neural networks in choosing the variables that you think contribute to injury risk and identifying points in your season where players get injured most. You can look back at the combination or interaction of risk factors and see what lead to the injury. Finally, set up an alert to let you know if the same combination of risk factors pop up again in the future you can react to reduce injury risk. I agree with this approach as there are so many examples of when practitioners are reactive to injury rather than being proactive like this to reduce injury occurrence.

factors based on each individuals performances and team performances. Then using neural networks in choosing the variables that you think contribute to injury risk and identifying points in your season where players get injured most. You can look back at the combination or interaction of risk factors and see what lead to the injury. Finally, set up an alert to let you know if the same combination of risk factors pop up again in the future you can react to reduce injury risk. I agree with this approach as there are so many examples of when practitioners are reactive to injury rather than being proactive like this to reduce injury occurrence.